Stories & Videos

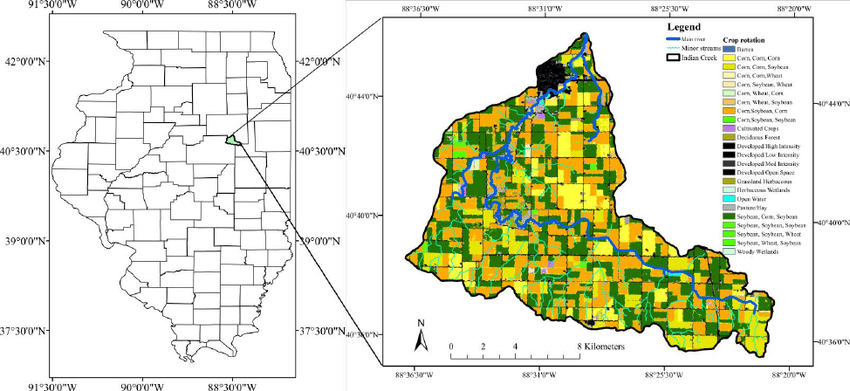

At Indian Creek, collaboration shifts local norms

Five years after a local steering committee met in Indian Creek watershed for the first time, more than 50% of farmland in the basin was in conservation practice.

Interest in best practices and stream health was high, and community-driven outreach had transformed the way nutrients were used on local farmland.

Strong local leadership

“Before any work on this project began, a diverse local steering committee was assembled,” says Chad Watts, project director. “Farmers, crop consultants, ag retailers, local conservation staff, bankers, and other citizens stepped up. From the start they had real decision-making power, and they’ve used it to make things happen.”

The project started after Watts’ organization, Conservation Technology Information Center (CTIC) received funding from Illinois Environmental Protection Agency to discover how conservation practices on 50% of farmland in an agricultural watershed would affect water quality.

“We amassed partners, then sat down to choose a watershed,” says Watts. “Our criteria were clear: 1) documented need or problem; 2) manageable size; and 3) a strong local partner. Indian Creek and Livingston County rose to the top, largely due to strong leadership at Livingston County Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD).

Personal invitations

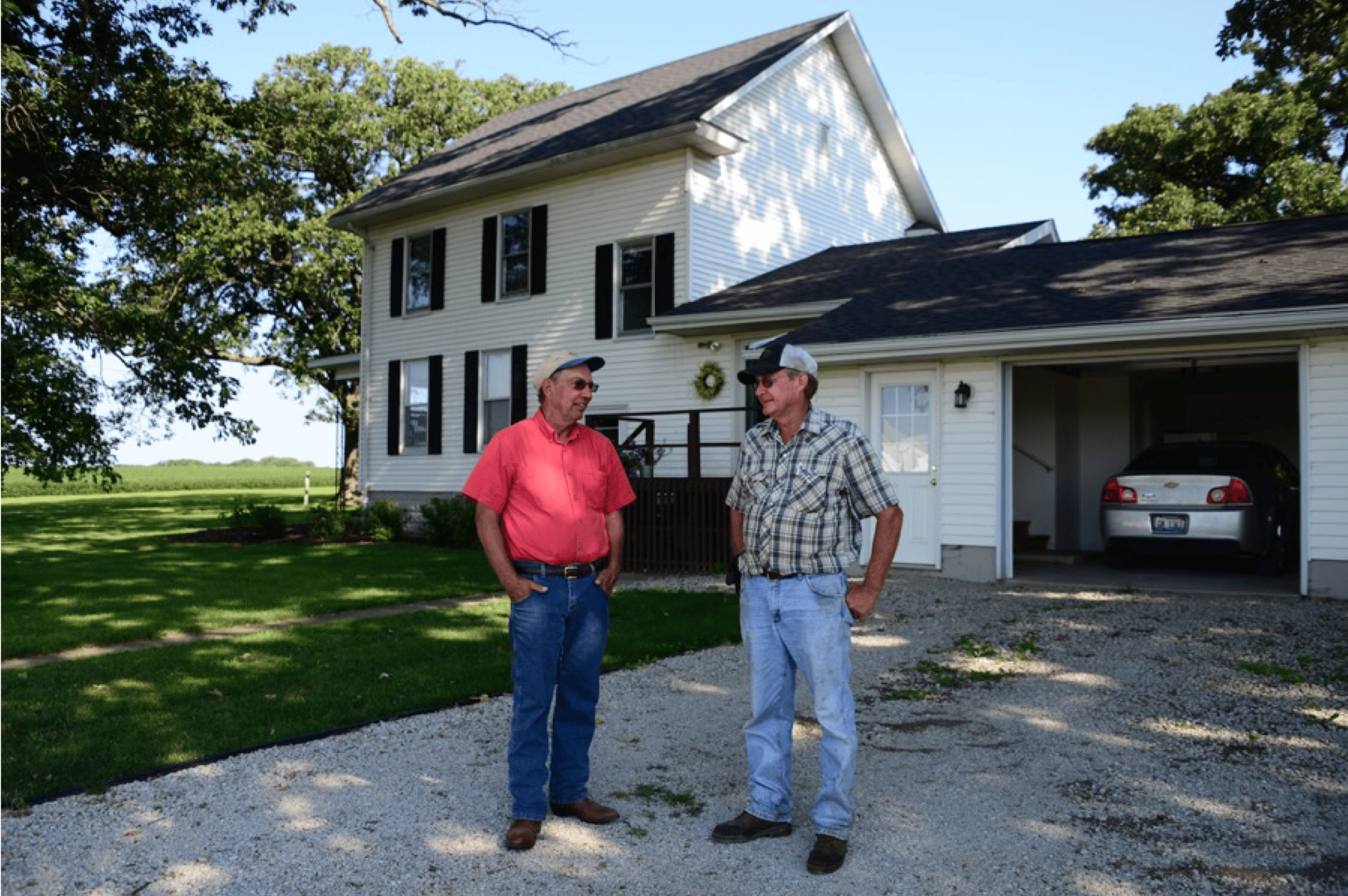

Outreach was a top priority. CTIC drew on existing relationships to bring in conservation and farm business partners who shared practices, products, and expertise. Livingston SWCD secured Mississippi River Basin Healthy Watersheds Initiative cost share dollars. The SWCD sent letters and made calls to every farmer in the watershed and Terry Bachtold, director, visited all 104 farmers to invite participation.

“Terry’s not a technology guy,” says Watts. “He gets in the car and goes to talk to people. He connects with them and people trust him. He’s been around a long time.”

Terry’s personal approach defined the steering committee. “I hand picked them,” says Bachtold. “I asked farmers I knew, farmers we’ve worked with in the past, farmers respected by neighbors. Everyone was invited to participate, but the core group of five to eight people had to bond and become close to make it work.”

Shared resources, goals

Agronomists, crop advisors, and ag retailers are important members of the core group. “They bring expertise to bear,” says Watts, “and a lot of ideas. Farmers pay their local retailers to give them advice. They’re trusted people. They jumped right in, and they’re all on board.”

“(Participating) allows me as a retailer to sit down with a farmer and not just say, ‘This is the regulation’,” says Mike Trainor, Trainor Grain and Supply, “but to say, ‘This is what we’re doing on farms.’”

Learning and action on the land included 23 demonstrations in the first three years. Cover crops, nitrogen application, and controlled drainage were the focus. Most demonstrations consisted of 20+ acre blocks of trials showing conservation technologies, nutrient application methods, nutrient formulations, or application timings. Winter meetings were held. Summer field tours the first two years drew more than 400 people. Water quality is monitored at watershed outflow for nitrate/nitrite, phosphorous, and total suspended solids.

“It’s honest. it’s open. It’s almost us teaching us, rather than somebody coming in and saying ‘I’m teaching you,’” says Watts. “Landowners are looking for ways to improve efficiencies. They know their farms and soil. They know the gaps. They enjoy being a good example, and many are now spokesmen for the practices and the project.”

Participants emphasize that while many things make the project successful, one important reason is that people like each other. “They have a good time getting together and talking about issues,” says Watts. “There are some real progressive people on the steering committee and they’re always bouncing ideas off one another. They’re open.”

Shared resources are also important. “The SWCD didn’t have to bring everything to the table. CTIC didn’t have to bring everything to the table. We’ve got this multi-layered sort of approach,” says Watts. “Everybody contributes something and we can all go home knowing we’ve done good things.”

Norman Harms, participating farmer, says, “Give it a try and get started, and try not to get too discouraged if you get too many no’s. It kind of builds on itself once you get going.”

— Story by Nancy North

Fishers & Farmers Partnership for the Upper Mississippi River Basin supports collaborative, local, farmer-driven work for healthy streams, farms and fish habitat. For more than a decade we have provided funds to projects in Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri and Wisconsin, as well as connection and leadership development for local teams, including this Iowa project. Learn about Fishers & Farmers Partnership funding and apply here.