Stories & Videos

Farmers lead for healthier soil and water

Post holidays, a farmer in the Upper Mississippi River Basin might choose to sit back and enjoy time with family and friends. The harvest is in after a season of record flood events.

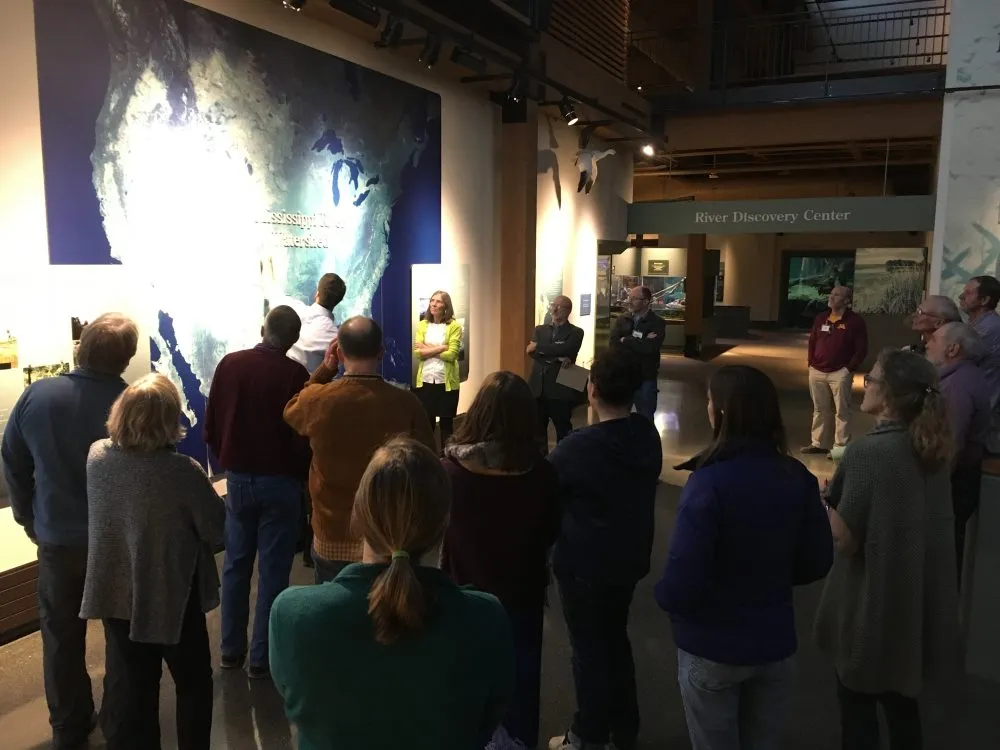

The crop now sits in elevators, ethanol plants, co-ops or river barges destined for markets. Some cover crops of rye are planted, and bales of alfalfa are rolled into hay ready to feed livestock through months of wintry winds. Yet, in Dubuque, Iowa, a group of farmers, fishers, watershed project coordinators, a planner, an excavator, and a crop consultant from across five states stands in front of an expansive floor-to-ceiling map of the Mississippi River Basin. As they point to where their farms and watersheds sit in this massive basin, they share stories of how their home areas impact the Mississippi River. Here, at the National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium, they learn from each other about challenges they face as leaders in their own agricultural watersheds, and explore solutions.

These citizens are key contributors to the Watershed Leaders Network, a workshop series and learning network sponsored by Fishers and Farmers Partnership. They listen to each other for new farmer-led ways to collaborate and improve soil health while protecting nearby waters in Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Missouri. Each person’s story is highly valued since this is new ground for all, addressing a complex issue.

Through thoughtful conversations, a common purpose surfaces among peers.

- How can they make a return on their investment while farming responsibly?

- How can they adapt new conservation practices in a timely fashion to address the steep decline in the quality of public waters?

- And how are they catalyzing other farmers to do the same?

The answers are as diverse as the types of soils and agricultural industries prevalent in each area. Yet a cultural change, in its infancy, has farmers re-examining what is good for the bottom line and their role in stewardship of land and water. This emerges in their conversations about cover crops and more.

Comparing notes on cover crops

“The reason I got into conservation practices is purely financial,” says Dave Gerber, a farmer who lives in the Boone River Watershed near Lu Verne, Iowa. The strip- and no-till practices Gerber has used for the last ten years on corn and soybean fields have paid for themselves; he saves $100 per acre in input costs. Now, he is trying out cereal rye as a cover crop to learn how it affects his bottom line. To begin, he is utilizing government programs for three years. Afterwards, he will know whether the practice can pay for itself. “If it saves me in fertilizer, herbicides, and increases my yields,” he says, “then, I’ll do it.” And if it doesn’t, he explains, it will be necessary to appeal for good stewardship which will take much more time and effort to cover the recommended acreage in his watershed.

Time is of the essence to meet nutrient reduction goals

To meet water quality goals in nutrient reduction strategies of the Upper Mississippi River Basin states, time is of the essence, points out Nancy North, Watershed Leaders Network organizer.

She prompts discussion among the group with statistics from a column in her parents’ local newspaper, the Des Moines Register:

“The state’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy calls for building 7,000 conservation reserve enhancement wetlands, but the state has about 70; it calls for 120,000 saturated buffers and bio-reactors but Iowa has about 60. How does the state go from a half-million acres of cover crops today to attain the 12 to 17 million acres that we need to meet the strategy?”

Why and how farmers lead cover crop efforts

Cover crops—non-commodity perennial crops such as rye, oats and radishes—are gradually being introduced into the landscape of the Upper Mississippi River Basin. They are grown to protect fields and streams, and to improve soil health and long-term productivity. These “third” crops cover the soil, hold it in place and increase organic matter over time. Landowners sometimes take advantage of cost-share programs offered by state and federal agencies to expand the number of cover crop acres or encourage experimentation. Why? Many benefits are reported: Soil health and productivity improvement, input cost reduction, forage availability, water and air quality improvement, and provision of wildlife habitat.

During this Watershed Leaders Network workshop and in the weeks following, participating farmers are curious to hear how others have kick-started efforts to make changes on their farms, and to interest neighbors in practices that improve soil and protect water. Tim Smith raises 800 acres of corn and soybeans south of Gerber, in the same North Central Iowa watershed. He and Karen Wilke, a watershed project coordinator with The Nature Conservancy, share photos of a field day on the Smith farm. At the event, neighbors see how cover crops and prairie strips work and how a bioreactor at the edge of one cornfield removes nitrates from the water. Smith and Wilke compare notes with other cattle and crop farmers, John and Sandy Scherder of the Peno Creek Watershed in Northeast Missouri, discussing what to watch for in the bottom line. Things they look for include the total number of tons of soil lost per acre each year from water and wind erosion, additional sequestration of carbon in the soil, and a reduction in the need for nutrient application.

To answer funding questions, Smith explains his funding came through the Mississippi River Basin Healthy Watershed Initiative, a program by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). In addition, he lists other partners including the Iowa Soybean Association and The Nature Conservancy. Compared to some other watersheds, Smith says, the Boone River Watershed does not have an organized farmer-led group to spearhead these efforts, so these organizations have reached out to get things started. As stories are shared, farmers who do take advantage of NRCS funding report having strong relationships with their local soil and water professionals. Other farmers, who are cautious of some of the strings attached, share how they are finding independent ways to get cover crops started on the land. All of them seem to share a preference to take the lead on this instead of being forced to do so.

After listening to the influence other farmers have had on their neighbors, Gerber, Wilke and Smith make it a priority to get more farmers involved and encourage them to try these practices. “In my area, we’re at the very beginning stages before we get to where the Mill Creek or Galena group is, but we need to keep stoking the fire,” Smith said, “and increase the awareness of the problem.”

Protecting the healthiest streams

John Scherder shares how he collaborates with Missouri Department of Conservation biologists Sherry Fischer and Chris Williamson to initiate cover crop use on Peno Creek area farms. He and 26 other producers, working together as the Peno Creek Cooperative Partnership, have planted more than 1200 cover crop acres in 2016. Peno Creek’s waters are clear and offer high-quality habitat for small mouth bass and rock bass, so efforts here are targeted to improve soil health and protect a relatively healthy stream system.

As Sandy Scherder shares a photo of their grandchildren playing in the stream, her husband John says, “We want to protect and keep what we have here.” Based on earlier reports from farmers initiating spring nitrogen applications in Central Illinois’ Indian Creek watershed, he wants to expand the work with additional farmers into a neighboring watershed focusing on nutrient management. During an evening gathering, crop consultant Wayne Solinsky, from Mill Creek Watershed near Stevens Point, Wisconsin, makes a point of connecting with Scherder on this.

Cost-effective nutrient management plans

“A nutrient management plan is a viable tool for farmers to save money,” Solinsky later explains. “Nutrient management plans can be a win-win tool for everyone. The fewer nutrients used, the more it stays on the farm and the less often it runs into the water.” For his clients, it’s about a maximum return of nitrogen ratio that doesn’t pay to exceed. “When you are looking at costs, they are giving up some yield, potentially, but economically, it’s not in the farmer’s best interest to get to the point of diminishing returns.” Solinsky observes that when his farmers give him accurate information and data on their practices going into the plan, they get valuable information out of it, and their collaboration is effective.

Solinsky accompanies an expressive farmer, John Eron, of Wisconsin’s Mill Creek Watershed, to Dubuque.

Additional field trips and networking

After two days of Eron’s enthusiastic stories about progress in the Mill Creek Watershed, several key leaders from Viroqua, Wisconsin, and Galena, Illinois accept invitations and make plans to attend a field tour of cover crops at the Farmers of Mill Creek Watershed Council annual meeting near Stevens Point, Wisconsin. “It’s nice to not work in a vacuum,” says Beth Baranski of Galena. Baranski invites the group to attend her community’s next public meeting, which will be lead by Galena’s League of Women Voters. She is coordinating local efforts to start a collaborative two-year watershed planning process for the impaired Galena River in the Apple Plum Watershed. This has local farmer support, as well as funding from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Together, she and her fellow community leaders are partnering with the local Rotary International club, as well, this winter to engage more people.

And so, as the snow accumulates and winter settles into these Midwestern states, the fields may appear to lay dormant. Yet, plans are in the making and inspiration continues to grow from a network of diverse neighbors, each with their own levels of expertise, working towards a new vision for real watershed leadership.

“It might be possible for me to be a part of the solution,” said Dave Gerber, “instead of just an observer.”

— Story by Anne Queenan

Fishers & Farmers Partnership for the Upper Mississippi River Basin supports collaborative, local, farmer-driven work for healthy streams, farms and fish habitat. For more than a decade it has provided funds, connection, and leadership development to projects in Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri and Wisconsin, including this Iowa project. Learn about Fishers & Farmers Partnership funding and apply here.